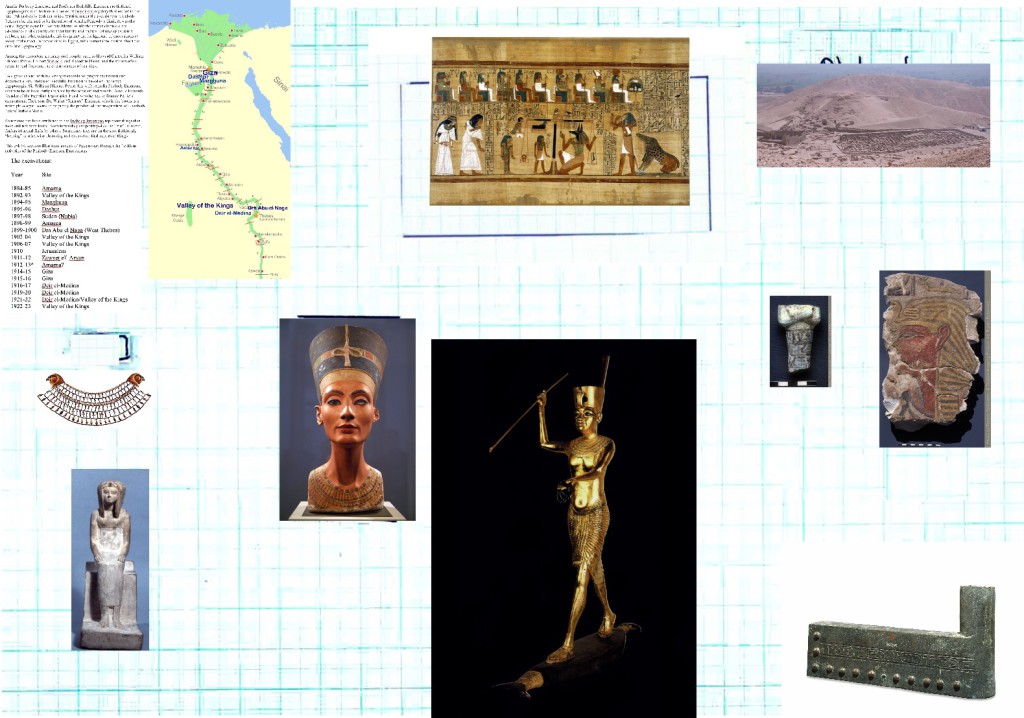

The Peabody-Emerson Excavations Virtual Exhibit (Display case sketch, 2.6 meters wide, 1.8 meters tall)

Amelia Peabody Emerson and Professor Radcliffe Emerson are fictional Egyptologists who feature in a series of humoristic mystery thrillers set in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Writing under the pseudonym Elizabeth Peters (who claimed to be the editor of Amelia Peabody’s diaries), was the actual Egyptologist Dr. Barbara Mertz. While the stories chronicle the adventures of the couple and their family and friends fighting spies, tomb robbers, and other criminals, this is against the background of excavations at many of the most important sites in Egypt, with correct information about the sites and Egyptology.

Among the characters are many real people, such as Howard Carter, Sir William Flinders Petrie, Herbert Winlock, and Theodore Davis, and the stories often relate to real finds and the circumstances of real digs.

To a great extent, with his strong standards for proper excavation and documentation, Professor Radcliffe Emerson is based on the famed Egyptologist Sir William Flinders Petrie. His wife, Amelia Peabody Emerson, seems to be at least partly inspired by the novelist and traveler Amelia Edwards, founder of the Egyptian Exploration Fund, who helped to finance Petrie’s excavations. Their son, Dr. Walter “Ramses” Emerson, who in the books is a noted philologist, seems to be purely the product of the imagination of Elizabeth Peters/Barbara Mertz.

Sometimes the finds attributed to the Peabody-Emersons represent things that have still not been found. Sometimes they are portrayed as the “true”, if secret, finders of actual finds by others. Sometimes they are on the spot fictitiously “helping” or otherwise observing real excavators find important things.

This exhibit seeks to illuminate aspects of Egyptology through the fictitious activities of the Peabody-Emerson Excavations. (Note: The objects are displayed in chronological order for Egyptian history, and not in the ostensible chronological order of the Peabody-Emerson excavations or the publication history of the books.)

The excavations:

Year Site

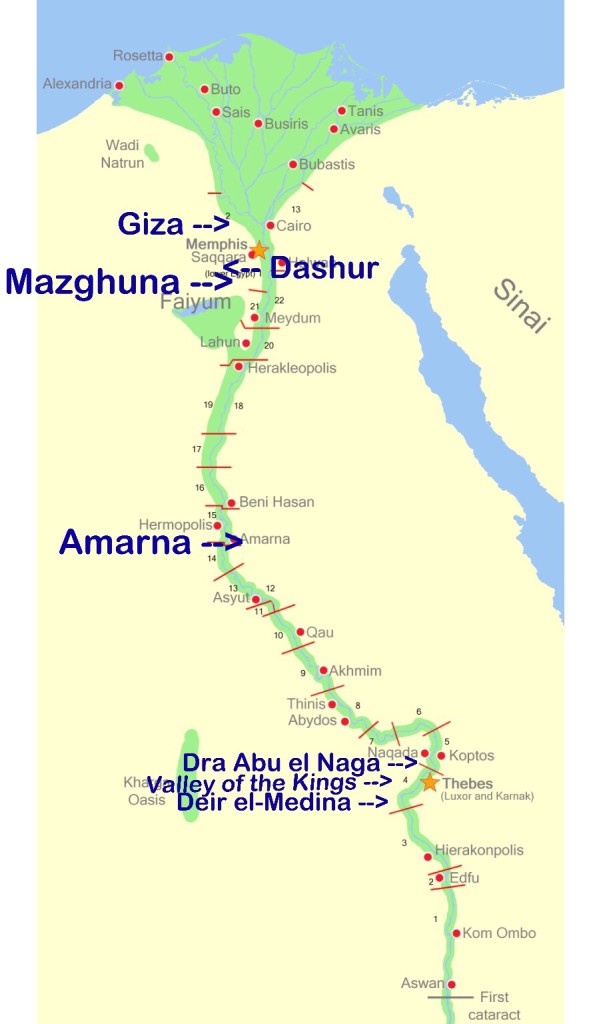

1884-85 Amarna

1892-93 Valley of the Kings

1894-95 Mazghuna

1895-96 Dashur

1897-98 Sudan (Nubia)

1898-99 Amarna

1899-1900 Dra Abu el Naga (West Thebes)

1903-04 Valley of the Kings

1906-07 Valley of the Kings

1910 Jerusalem

1911-12 Zawyet el’ Aryan

1912-13 Amarna

1914-15 Giza

1915-16 Giza

1916-17 Deir el-Medina

1919-20 Deir el-Medina

1921-22 Deir el-Medina/Valley of the Kings

1922-23 Valley of the Kings

Map of some of the more notable Peabody-Emerson excavations (Image adapted from Kiddle.co, under Creative Commons licence )

Thanks to John Taylor of the British Museum and Silvia Mosso of the Egyptian Museum in Turin for kindly answering my questions about objects in their collections.